If you’ve been paying attention to any news lately, you’ve probably seen the headlines about money and happiness. And if you’re human, you’ve probably wondered: Does money make you happy? After all, who hasn’t thought about how much happier they’d be if they only had this salary or that inheritance? Surprise: The answer is way more complicated than you think. But we like complicated around here—so we’re ready to dig in.

A Comprehensive Look at the Relationship Between Money and Happiness

In case you’ve missed out on the money and happiness stories, here are some numbers you’ll see floating around. First, in 2010, the media sited a study that put the price of happiness at an income of $75,000 per year. (Note this is per individual, not per family or couple.) Then this year, news broke out that it really takes $105,000 annually to reach your full happiness potential. Get your grind on, readers, because this seems to only be going up.

Except that’s not the full story. And that’s actually not even an accurate representation of the research. That’s where we come in.

We’re going to help you make sense of the news about money and happiness. What does that mean? We won’t tell you exactly how much money you need to make you happy or what to spend it on. But we will share the most reliable, research-backed ways to align your spending habits with your happiness and well-being.

Here’s what you’ll find in this research-backed guide to money and happiness:

- What those happiness-salary goals you’ve seen in the news really mean

- How spending money can backfire and negatively affect your happiness

- How spending money can make you happy if you do it in certain ways and…

- What questions you can ask yourself before making a purchase, based on the most important research

Read on for the full story or skip ahead to the section that interests you most. We won’t be offended either way.

1. The real story behind the salaries for peak happy

Some of us let out a big sigh of relief when we found out that happiness happens at certain incomes. If you just make $105,000 annually, you’re happy. It’s a tangible and straightforward goal, right? Well, not exactly.

Firstly, that’s not what the research is saying. Pulling data from 1.7 million people worldwide in the Gallup World Poll, the researchers found that people who earn $95,000 per year ($105,000 for the US in particular) are just as satisfied with life as people who earn more. So it’s not saying that you can’t be happy at other incomes or that you will be the happiest you can be at that particular one. Rather it’s saying that your happiness increases in relation to your income only up to that salary level. Once you cross that line, you’re not going to continue to be happier with continual salary growth. So money and happiness are related but not exponentially. In fact, sometimes more money means more problems. (Sorry, we had to.)

And this is a good thing. It confirms that there’s more to life than the accumulation of wealth. Let’s dig deeper.

Why did the number change from $75,000 to $105,000?

The new study is a more accurate follow-up to the original 2010 report about $75,000 being the true happiness salary. So why the number jump? Think inflation adjustments (i.e., $75,000 in 2010 = $86,000 today) and more precise statistical techniques (i.e., averaged exact incomes instead of ranges), but the most important difference is easy to miss. The $75,000 and $105,000 figures are about two different kinds of happiness: emotional well-being and satisfaction with life. And once you know that, you’ll see that the studies come to similar conclusions:

- Emotional well-being: ~$75,000 The two studies agree on how much income you need to max out your emotional well-being, which means the mix of positive and negative emotions you experience day-to-day.

- Satisfaction with life: ~$105,000 Satisfaction with life is a long-term evaluation of one’s own life, assessed by asking people where they stand on a scale of the worst to best possible life. The two studies both find that maxing out life satisfaction requires a higher income, but only the new study found an upper limit where more income no longer adds to your satisfaction.

But what happens to happiness at higher incomes?

Surprise, surprise: Happiness declines for incomes above the turning point of ~$105,000, according to the 2018 study. It only happens in five of the nine world regions (including the United States) and only for long-term life satisfaction. But it’s still sort of a shock.

What are some other limitations of the studies on salary?

- It’s key to remember that these reports study income differences on average, and not income changes over time. Raises and pay cuts definitely impact people’s happiness, but those changes aren’t reflected in these reports. Instead, these reports average the data across millions of people to see at what income levels there are average differences in happiness.

- These survey results give you plenty to ponder, but the authors can only speculate about the causes behind the happiness plateaus and declines that they reveal. So they’re giving us numbers, not reasons. Let’s turn to related psychology research to seek deeper explanations.

2. How money takes a hit on your happiness

Enter the age-old question: Can money buy happiness? Yes. And also no. Money can enhance your happiness or it can detract from it. Here are some reasons it can bum you out:

- Hedonic adaptation: Huh? Hedonic adaptation means that your emotional (hedonic) experiences change over time (adaptation) even when your situation stays the same. For example, you might initially feel happier when you buy that new espresso machine. The first few times you use it, you get a rush of pleasure. But after a few weeks? The exquisite coffee fades into the humdrum of your morning routine. That’s hedonic adaptation, and it’s the root cause for why the relationship between money and happiness isn’t simple.

- Time stress: Higher incomes usually demand longer working hours, which in turn result in more stress. High earners perceive more “time stress,” or stress from feeling like they can’t get all of their tasks done, for the same amount of time spent working as those who earn less. The theory is that the more money you earn, the more valuable you feel your time is, and the more you stress out about managing it.

- Too much value on material things: Since the mid-1980s, studies have revealed that people with “materialistic values” are less happy and satisfied with life. Why? They overestimate the happiness they’ll get from purchases and don’t realize how quickly it will fade. See also: hedonic adaptation.

- Social comparisons: We’ve known since the early 1970s that social comparison can diminish how good you feel about things you buy and events in your life. But how can you stop yourself from comparing your car to your neighbor’s car? Or your job title to the promotion your friend just earned? We’re getting there.

The best solution to these issues is to shift your mindset about money.

3. How spending money strategically can make you happy

Spend your money on experiences, not on things.

Researchers call these experiential purchases. A breakthrough series of studies found that people get more happiness from an experiential purchase than a material purchase. The same study found that this pattern holds true or even increases for higher earners. So this is one strategy that works for all of us. And there are a whole lot of reasons for it.

- Experiences are great for your social life: Yes, doing things with your friends is good for your social life. Additionally, researchers have found that people who spend their money on experiences are more likable and more fun to talk than people who spend their money on stuff. Both during and after a given purchase, experiential spending helps you build and sustain friendships.

- Experiences get better over time: Memory is weird. Even though your hike involved backaches and boredom, those unpleasant moments tend to disappear when you reflect on the experience. Instead, you remember the view and the satisfaction of making the climb. Even weirder? The view might be more breathtaking in your memory than it was in real life.

- Experiences are harder to compare: It’s easy to figure out if your car is more or less valuable than your neighbor’s car. But do you ever wonder if your bike ride was more or less valuable than your neighbor’s day trip? It’s not as easy to compare your unique experiences, and that makes you less likely to regret experiential purchases.

- Experiences = identity: People tend to think of their experiences as more important to who they are than their possessions. And it goes both ways. Other people believe they learn more about your true self from your experiences, not your things. In the researchers’ words, “You are what you do, not what you have.”

What is the difference between an experiential and a material purchase?

Is a harmonica a material thing because you can hold it in your hand? Or an experience because of the hours of challenge and play it will provide? The researchers refuse to answer, and instead, they leave the distinction up to you. But we want answers! We know.

Think about it like this: An experiential purchase is anything that you buy mostly for the life experiences it provides. Even a new watch can count as an experiential purchase if it’s part of your experience getting dressed up and exploring nightlife. (And we promised we wouldn’t tell you how to spend your money, so go on with your trendy timepiece.)

Aside from experiences, how else can you spend your way to happy?

- Make the most of your free time: People who spend money on “time-saving services” report greater life satisfaction than people who don’t. What are time-saving services you ask? Things like cleaning the house, doing yard work, even cooking. The reason? These things buy you extra time and push back against the time-stress effects of money. If you can afford it, it’s worth considering how much happiness you’ll gain by trading some of your dollars for minutes.

- Spend on others: Spending money on others—through charity or simple generosity to friends—gives your happiness a greater boost than spending money on yourself. Researchers call it the “prosocial spending effect,” and it holds up to lab, field, and survey studies since it first came on the scene in 2008. (There’s a research scene, right? Right.)

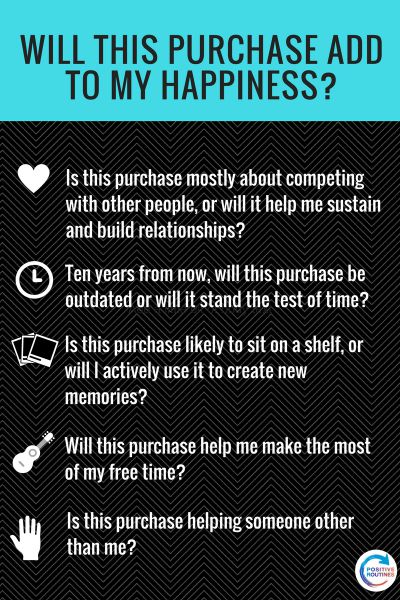

4. Money and happiness checklist

You might not be planning to memorize this whole guide (though you definitely should), so we did our best to pare down the research into a short checklist of questions. Ask yourself these whenever you’re making a spending decision:

- Is this purchase mostly about competing with other people, or will it help me sustain and build relationships?

- Ten years from now, will this purchase look old and sad compared to the latest and greatest version, or will it stand the test of time?

- Is this purchase likely to sit on a shelf, or will I actively use it to create new memories?

- Will this purchase help me make the most of my free time?

- Is this purchase helping someone other than me?

We hope we cleared up how money relates to happiness—or at least demystified a part of it. Remember that how much money you make isn’t as important to your happiness as how you spend your money. So don’t get caught up in the more-money, more-happiness trap. You can do a lot for your own well-being with what you have right now. And maybe that’s the most uplifting part.

Your turn: What surprised you most about the relationship between money and happiness? Tell us more in the comments.

If you like this article you’ll also like The Science-Backed Benefits of Forgiveness You Need to Know

Author: Scott Trimble

Scott researched human motivation at The University of Texas at Austin. He spends most of his time traveling, reading, teaching, and writing.

Brian T Stark says

Brian T Stark says

April 17, 2018 at 1:12 pmGreat article and a great perspective on the relationship between money and happiness. I once had a multi-millionaire friend (now deceased) who was always depressed. Why? Because he never new whether other people liked him “for him” or “for his money”. Fortunately, in my case I knew him well before I had any idea of his wealth. In addition, because he didn’t need to work to sustain his lifestyle, he always was frustrated with how to spend his time productively.

Chelsey says

Chelsey says

April 17, 2018 at 6:44 pmThanks for the comment, Brian! Money can complicate a lot of things—both for the people who have it and the people who wish they did. It doesn’t provide the meaning we seek, but it can be a resource to help us get there if we use it the right way. I’m sure the research will provide even more insights into this complex relationship in the future. We’ll be sure to keep you posted. Thanks again!